Lutf hai kaun si kahani mein / Aap beeti kahoon ya jag beeti…

(What story is more pleasurable? Shall I tell my own, or the world’s?)

– Mirza Muhammad Hadi Ruswa, Umrao Jaan Ada

Mirza Muhammad Hadi Ruswa’s1 novel burst onto the Urdu literary scene as the nineteenth century was fading out. It has never gone out of print since, and has been adapted for the screen and stage several times.

Its enduring impact isn’t completely rosy, however. The chief complaint that scholars of music and history I spoke to for this essay have had is that a nineteenth-century novel is considered the source of irrefutable historical fact by many who engage with it. They aren’t wrong; I find that any conversation I have about Umrao Jaan Ada is suffused with questions about the identity of the eponymous protagonist.

‘Which do you think is true?’ Himanshu Bajpai, a dastango, or storyteller, from Lucknow—the city Umrao Jaan’s story is set in—asks me: ‘Was she real, or was she fictional?’

I am deep in the rabbit hole that I had sworn not to go down, and looking at contradictory arguments by scholars—some claiming that ‘Umrao’ was not Ruswa’s invention, but a real-life informant, while others, pointing to the blatant inconsistencies and historical inaccuracies in her story, argue that there is no question of her being a real-life person.

‘What do you think?’ I counter.

‘I think both are right. And I think both are wrong,’ he answers.

Entangled in the undoubtedly alluring question of whether we are hearing an ‘authentic’ voice is another question, which is – what are we missing? Certainly the authorial voices of tawaifs themselves, that have for the most part been deliberately erased, stomped on, spoken over.

Audiences are enchanted by the undeniable affective powers of music, dance and poetry—the arts associated with the popular-culture idea of the tawaif figure. Besides, pity, disgust and voyeurism all surround the tawaif’s sexuality, which is today understood primarily as sex work. Altogether, these many projections onto the persona of the tawaif in effect erase the personhood of individual tawaifs, with their polyphonic experiences and trajectories.

Our collective desire to hear directly from a tawaif—a catch-all term for the North Indian courtesan performer—is understandable. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could irrefutably prove that Umrao Jaan’s tale was real, told to us unvarnished, reaching its tentacles across the vagaries of time and place? A ‘true’ story that gives us some certainty?

It is not the search, but the source that we must question.

The remains of Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Awadh, lie in the Sibtainabad Imambara in an area of Calcutta called Matiaburj. It is almost all that remains of Shah’s long exile in the city after he was deposed from his throne by the British. After his death, the Empire was thorough in erasing his existence, thorny and problematic as he had been to its project from the beginning.

At the tomb in Calcutta today, which is hushed and empty but for its caretakers, is also a standing poster featuring Begum Hazrat Mahal. She was one of Wajid Ali Shah’s many wives, remembered for her pivotal role against the British during the Rebellion of 1857.

While the rebellion was raging in Lucknow, in the name of their son, Birjis Qadr, Shah was already in Calcutta.

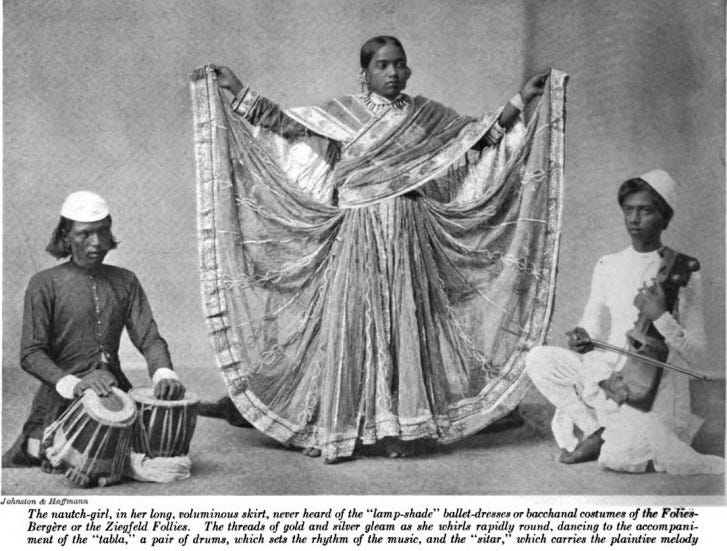

One of the reasons the Empire gave for deposing the king, under whom the performing and literary arts flourished in Lucknow, was his fondness for the company of professional women performers. It is another matter that Europeans of the time in South Asia had hosted, enjoyed and extensively written about ‘nautches’, performances of live music and dance by the very same communities of women.

Begum Hazrat Mahal too was once a ‘dancing girl’ in Shah’s Pari Khana, or Abode of Fairies—the typically baroque name for the space where he employed a vast number of women artists. Some of these women became his lovers, and some his wives. Before she was renamed, Hazrat Mahal was known as Mehak Pari. Once she became one of Shah’s muta’hi (lower-ranked) wives and the mother of his son, she also observed purdah.

While Shah’s mother and some of his other relatives and courtiers made an ill-fated journey to Queen Victoria’s court to petition for the return of the kingdom of Awadh, Begum Hazrat Mahal fought in the doomed rebellion. She lost and fled to Nepal, where she is buried.

Ruswa’s Umrao, as a high-status, highly educated and highly skilled performer, is attached to the royal court of Awadh. During the Rebellion, which transforms both her life and her city’s life, she is invited to perform at Birjis Qadr’s investiture.

The Rebellion is the pivotal event in the novel, filtered through not only Umrao’s experiences, but the experiences of other courtesans in the establishment run by Khanam Jaan, the head of their household.

One critic, Khurshid ul Islam, suggests that Lucknow—seen in the novel at its zenith and in its decline, with its descriptions of the ‘culture of poetry, music, mushairas, evening soirees, imambaras, marsiyas, Muharram, Holi, the fair at Aish Bagh and so on’—is the protagonist of the novel. Author and critic M. Asaduddin, doesn’t disagree: ‘Ruswa is not interested in the courtesans in the Chowk for their own sake but because of the way they bring to light different facets of the socio-cultural life of Lucknow and the countryside around it.’2

‘The theme of the novel is certainly the fall of Lucknow and its ethos at a certain period in Indian history,’ he adds.

Ruswa himself was born in 1858, the year the Rebellion failed and Lucknow was lost. According to Khushwant Singh and M.A. Hussaini’s introduction to their translation3 of Umrao Jaan Ada, he had the reputation of being an ‘eccentric’ man, trained in many languages, and especially passionate about ‘chemistry, alchemy, and astronomy’. He was also, of course, a poet and prose writer, whose first work – ‘a long poem recounting the romantic tale of Laila and Majnun’ was published in 1887.

Ruswa wrote both ‘literature’ and pulp novels, and also translated several Victorian ‘penny dreadfuls’ to Urdu. Oldenburg reminds us that he was a crime-fiction writer, and published a series of sensational novels, featuring murderous characters, and titled Khooni Aashiq (The Killer Lover), Khooni Joru (The Killer Wife) and Khooni Shahzada (The Killer Prince).4

Urdu poetry was already famed for its transcendence, especially at the hands of its two most feted poets, Mir Taqi Mir and Mirza Ghalib, but also through the culture of the mushaira, or poetic gathering, in which enthusiasts gathered to recite their own verse. Urdu prose had hitherto been characterised by the tradition of the qissa and dastaan—speculative, often epic, fiction that dealt in tales of fantasy, magic and adventure, as Asaduddin notes.

Ruswa was writing during the flowering of a new literary age for Urdu prose. Asaduddin records the coming of the printing press, the rise in the literary work published in periodicals, and the emergent literary concerns of moral didacticism and social reform. The Victorian realist novel, too, had an impact on this emerging culture. Writers could get paid per page, and undoubtedly Ruswa wrote for financial gain too.

Umrao Jaan appears in three of Ruswa’s fictional works—an unfinished early novel called Afsha-e-Raaz, in which she is quite different in physical appearance and personality from the character widely known through the immediately successful and still enduring Umrao Jaan Ada, published in 1899. Exactly one month after the publication of Umrao Jaan Ada, on All Fool’s Day, Ruswa published Junoon-i-Intezaar, in which Umrao takes ‘revenge’ on Ruswa for telling the world her story, by in turn publishing the story of his personal life for public consumption.5

Both Ruswa’s games of self-invention as well his invention of Umrao as a character are crucial to our present-day understanding of this story—one so influential that I have been asked to write about it over 120 years after it first appeared.

Katherine Butler Schofield6 has traced the widespread usage of the word ‘tawaif’ to the 1800s:

‘Generally speaking, until the late eighteenth century different communities of female (and male) performers were enumerated separately under their vernacular caste/community names,” she writes. “The earliest use I have found of tawaif in an English source to mean “courtesan”/“dancing girl” is in John Gilchrist’s 1787 Dictionary, in which he merely listed tawaif as one of several community names for courtesans/female dancers. But by 1813 Thomas Williamson used tuffah (taifa) for “dance troupe” indiscriminately.’

But if ‘tawaif’ as a word presents a problem, the English word ‘courtesan’ proves even more inadequate.

‘(It) fails to capture the diversity of this community in South Asia, which runs the gamut from highly trained and refined court musicians/dancers/poets to street performers who entertain at festivals and weddings, instead creating a discursive stereotyping or “totalizing”,’ writes Amie Maciszewski.7

In reality, these were vastly diverse, hierarchical, caste- and clan-based communities of matrilineal performers. The complex kinship systems of tawaif communities became regulated and codified under the racist colonial regime. Some communities of performers were classified as ‘criminal tribes’, and to this day live with the stigma of such classification in a society already deeply stratified by a punishing regime of caste-based bigotry and systematic deprivation.

There are also many kinds of different public performers who are not necessarily tawaifs. However, in the popular imagination, tawaif communities have successfully become conflated not only with each other but also with sex workers.

The roots of this flattening of identities go deep, and there are a number of impulses that govern the stigmatisation and marginalisation of women public performers. One such impulse is, as scholars such as Sarah Waheed, Partha Chatterjee and Lata Mani point out, the ‘women’s question’ that began to plague reformers and nationalists from the nineteenth century onwards. 8

Women’s sexuality and behaviour became intricately linked to the ‘honour’ of the nation, and scholars say that, as a result, a strict segregation occurred between the private, domestic sphere (to which women were relegated) and the public sphere. Any woman performing for the ‘public’, therefore, became unacceptable within the frame of this logic, and had to be ‘reformed’ or ‘rescued’.

Another major influence, of course, was the colonial regime.

Schofield speaks to me of the context of the moral reform that the British brought in to India, which later began to flourish among Western-educated Indian middle-classes. In the 1830s, with the rise of evangelical religion, the Empire assumed critical stances on gender and slavery. At the same time, British civilians in India continued to exploit Indians for indentured domestic labour.

After the Rebellion of 1857, the British East India Company was removed from its position of control, and India came directly under the rule of the Crown. ‘There was severe hostility from the British towards anything that smacked of the old regimes of Lucknow and Delhi,’ Schofield says. This included animosity towards high-ranking tawaifs, some of whom had actively taken part in the Rebellion, and whose salons—public spaces where Indian nobility could meet—were seen as suspect.

They reacted by promulgating laws designed to surveil and control the Indian population, including the Cantonment Act of 1864 and the Contagious Diseases Act of 1868, under which all performing women were classified as sex workers and subjected to harsh regulations, including invasive bodily examinations.

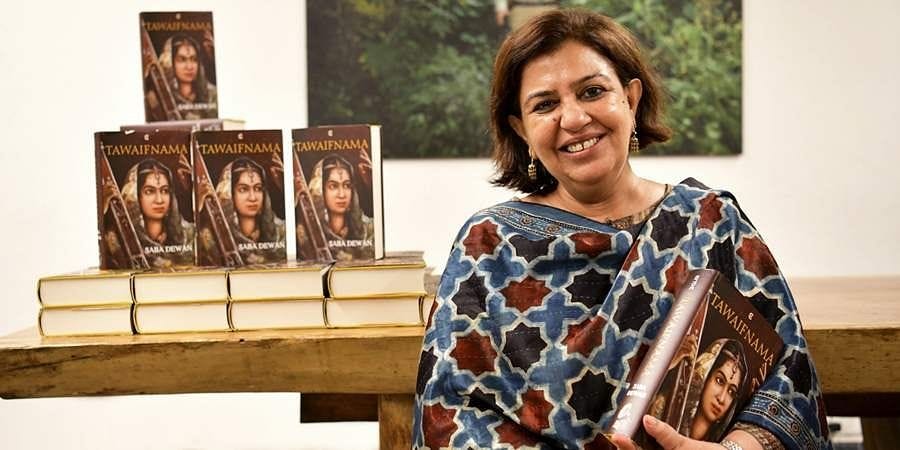

‘Colonial law-making (…) contributed substantially to the dissolution of the autonomy and privileged position as independent women of substance that courtesans had customarily enjoyed,’ writes Saba Dewan.9

‘By the third decade of the twentieth century, however, a new way of speaking and writing about the “fallen woman” emerged within the Urdu public sphere. This social critique heralded the prostitute-courtesan as an ethical figure struggling against an unjust social order and the moral tyranny of self-appointed community spokesmen. In this literature the taw ̄a’if appears as a figure of political desire. The critique presented by the voice of a fictional taw ̄a’if is one that sounds like an ideal citizen as imagined within a secular nationalist framework,’ writes Sarah Waheed.

It is against this wide and complex history that we need to isolate the reception to one aspect of Umrao’s story—the fact that she is kidnapped as a child and trafficked to the kotha. It is particularly necessary to investigate this plot point because, as Veena Oldenburg suggests, it has led to the popular perception that tawaifs are mostly kidnapped, and:

‘… that the tawa'if were linked to a large underground network of male criminals who abducted very young girls from villages and small towns and sold them to the kothas or nishat-khanas (literally, pleasure houses). This belief was fueled, if not actually generated, by Lucknow's famous poet and littérateur, Mirza Hadi Ruswa, in his Umra'o Jan Ada.’10

Conversations with Dewan and Schofield revealed to me that Ruswa was evidently playing on the moral panic around child slavery and trafficking that was at a fever-pitch in his own time. What happens to Umrao is not impossible, but it is far from typical.

The vast majority of tawaifs were hereditary. In tawaif families that did not have enough performing women, girls were adopted or indentured. In some cases, they were treated like daughters of the family, but Dewan emphasises this was not always the case. However, very rarely would these girls have been kidnapped.

‘They did not kidnap children,’ says Schofield too. ‘There are rare criminal cases of children being kidnapped into sex work, but no evidence that those children were kidnapped to dance and sing.’

This was a time of great deprivation, poverty and famine, during which poor families were forced to give up or sell their children, who were then put to work in all kinds of households—including British and Indian royal and noble households. It was also a time during which the age of consent in India was twelve (having been raised from ten in 1891). British moral panic conveniently ignored the exploitation of children in elite households, and concentrated on the adoption or indenturing of girl children by tawaif families.

In the later part of the nineteenth century, the so-called ‘anti-nautch’ campaign gained momentum. Performing women were ‘seen on the one hand to be enemies of Indian culture and society, and on the other, as helpless victims of exploitation. There was increasing pressure on both Indian and British elites to refrain from holding nautches or to boycott them,’ writes Anna Morcom.11

Indian social reformers and nationalists accepted the British view that performing women needed to be reformed, writes Ruth Vanita. ‘This resulted in some courtesans getting married and hiding their supposedly shameful past, while many others became sex workers.’

In 1952, the abolition of the zamindari system resulted in the loss of royal and noble patronage for these performers, as Vanita notes.

By the early twentieth century, the process of appropriation of the musical repertoires associated with tawaifs had begun in earnest. Saba Dewan’s film, The Other Song, traces one ramification of this appropriation—the changing of song lyrics considered too raunchy or erotic to words that were less risqué. The impulse was to reclaim a glorious golden past, which revivalists maintained had been tainted by its association with performing women (as well as male Muslim hereditary musicians).

Also in 1952, Indian Minister for Broadcasting B.V. Keskar declared that those whose ‘private life was a public scandal’ were not welcome to sing for that venerable institution, the All India Radio. This declaration sums up the newly formed Indian nation’s attitude towards hereditary women musicians who had nurtured and shaped Indian music and dance for centuries. India took government patronage away from those who would not deliberately erase their own histories. Only those who fit into the construction of ‘ideal’ Indian womanhood—monogamous, married—were welcome.

Does this mean that tawaif performers up and disappeared?

On the contrary, as countless examples show, they continued to perform and enriched every new performance medium—the gramophone, the radio, the theatre and the cinema—with their considerable skills. In each new medium, they were eminently qualified to succeed, and in each, they played pioneering roles. In all of these spaces, they also fought the moral hypocrisy of reformists and revivalists, who wanted their repertoire but not their person.

They also continued to organise politically, just as many of them had during the Rebellion of 1857. They gave to the freedom struggle their own wealth and resources, even as nationalist political parties worked to marginalise them.12

Tawaifs employed their skills to negotiate with a system that was increasingly hostile to them, while still needing their considerable skills, at least until ‘respectable’ women could completely appropriate these artistic talents.

‘What remains to be documented properly,’ says Schofield, is ‘… how they move to the cities and they move into industries, where their skills are invaluable.’

A classic example is Begum Akhtar, who worked in virtually every single one of these mediums—as a court- and salon-based courtesan, as well as a gramophone artist, a singer-actress in the theatre and films, and a radio and concert performer. Akhtar also bent the rules, continuing to perform even after being ‘respectably’ married to a taluqdar and barrister. Akhtar’s massive impact on the ghazal and thumri forms—a legacy of her training as a great tawaif performer—reverberates to this day.13

Studies of contemporary communities of tawaif performers have shown how a moralistic discourse pushed them further and further away from the arts their families practised and shaped for generations.

Instead of trying to force-fit extremely diverse tawaif histories into one kind of narrative—whether empowering or disempowering—what if we were to turn our lens towards the State response to them?

What if, instead of the punishing consequences of Gandhian nationalism, or reformism, or revivalism, which saw their presence as polluting to the arts, they had been given the respect due to them as practising artists?

What if, with the fall of feudal patronage systems, their work in the creative industries was encouraged, instead of being appropriated and ‘sanitised’?

What if non-monogamous sex work and monogamous marriage were not seen as the only two options for women as the new nations of India and Pakistan came into being? What if tawaifs had been freed from the need to please or seduce male patrons, or even to marry ‘respectably’, and simply encouraged to perform for a mixed audience in whatever medium they wanted to work in?

What if Umrao wasn’t expected to ritually speak ill of herself in the course of telling her story?

For our purposes, it is also crucial to remember that someone like Umrao—in Wajid Ali Shah’s Lucknow (until he was deposed in 1856)—was living in a city and cultural context where tawaifs could and did amass fame and fortune. Importantly, she was also in the highest echelons of tawaif society. There existed a complex hierarchy among tawaif communities, and also within each courtesan establishment. Although scholars agree that upward mobility was possible, even within a single kotha, or salon, lived women whose power depended on a number of factors. The kotha is not simply a group of tawaifs, but an entire household headed by its matriarch.

Saba Dewan, whose epic non-fiction book, Tawaifnama, tells the story of modern India through telling the story of several generations of one tawaif family from Banaras and Bhabua, tells me of these complex dynamics within the household. She differentiates first of all between daughters of the chaudhrayan, or nayika (the head of the household), of the salon and those girls who were indentured or adopted into the establishment. Then there is the important difference between the performing women and the women who didn’t perform. The former had far more power than the latter because the entire household was dependent upon their earnings.

There is the hierarchy between sons and daughters, too, explored in Tawaifnama and also highlighted in Veena Oldenburg’s essay about women performers in Lucknow in the 1970s. In a matrilineal system, all the property and money is inherited, of course, by the daughters—and it is partly this inversion of the usual patriarchal order that Oldenburg elaborates on in her essay. But while her influential essay styles tawaif culture as a ‘lifestyle of resistance’ to the patriarchy, subsequent fieldwork like Dewan’s has shown that the reality is more complex.

The kotha can of course be a space of affirmation and interdependence, where women can perform and come into their own as artists. At the same time, Dewan says, ‘… it can also be as exploitative as any other space.’ Tawaifs don’t exist outside of the patriarchal and feudal social system, Dewan finds. ‘They are not at all like ascetics. They are family women, with entire armies of dependents they feed.’ Like in so many South Asian families, it is the daughters-in-law that are among the most exploited in tawaif households too, Dewan discovers.

There are also hierarchies among performing courtesans. Some tawaifs are focused mostly on performance, only needing to take on one patron or perhaps a few patrons. As we go lower down the social and economic hierarchy, though, the ratio of sex work as opposed to performance begins to increase.

Richard David Williams talks about the multi-storeyed salon depicted in Umrao Jaan. ‘Umrao would have been on one of the higher floors and would have been pretty inaccessible to most people. But what about the women on the lower floors? I am pretty sure they were not composing ghazal, and didn’t have as much of a choice when it came to picking their patrons,’ he says.

Oldenburg’s essay was an extremely important counter to all kinds of propaganda—reformist, revivalist, colonial, nationalist—that had plagued tawaifs. It was a new framework with which to think of them, as performers and as people with agency who had complex relationships with each other and the world. This was a crucial pushback to narratives that looked at them either as victims with absolutely no agency, or as dangerous figures that ‘polluted’ the social fabric. But it also led to the development of a certain lens that looked at them as proto-feminists. It’s an extremely attractive lens, because it paints a picture of powerful, tax-paying, property-owning women kicking patriarchy’s ass. It shows the kotha as a space of refuge from feudal patriarchy.

When I first started researching gender and performance in South Asian history seriously, it influenced me too, as it has influenced generations of researchers. But subsequent fieldwork has revealed that both lenses—either no agency or complete agency, either total disempowerment or proto-feminism, either completely enslaved or completely liberated—are inaccurate.

The reality lies in the middle, and often depends on several factors, including a tawaif’s ability to earn and make a name for herself as an artist. It also depends on social location. In the family that Dewan writes about in Tawaifnama, exist both tremendously successful tawaifs who chose their own lovers and a young girl who was repeatedly raped by men she never consented to take on either as patrons or lovers.

When we think of the performing woman in South Asian history, we think of her as performing for the ‘public’ in some way. Here, we understand as ‘public’ anyone not related to her, including powerful and wealthy patrons such as kings.

It is undoubtedly true that hereditary communities of women performers were central to music- and dance-making in North India for centuries. Scholars have argued for decades that the most elite of these women were highly educated and therefore often highly literary.

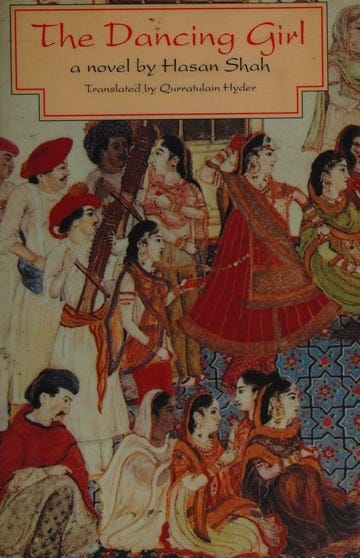

Over a hundred years before Umrao Jaan Ada was published came Nashtar, a novel in Persian by Hasan Shah, with Khanum Jaan—another performing woman—as its protagonist. This text, as historian Saleem Kidwai points out, shows us the rigorous literary training that women working in mobile encampments (‘deras’) had in multiple languages. ‘All the girls were well educated, prominent in their repertoire being the Persian ghazals of Hafiz. They knew how to sing, dance, and most importantly, converse. (…) Here was a group of small-time deredaar girls who spoke to each other in Kashmiri, pondered over the meaning of Persian ghazals, danced, sang Indian folk songs with joy and managed not only to negotiate with European men but debate with them about the meaning of Persian couplets.’14

And yet history shows us that the production of music and poetry was not the sole domain of the tawaif. Williams has noted, for example, the inclusion of many different kinds of women (both ‘public’ and ‘respectable’) in tazkiras, or anthologies, of Urdu poetry.15 This starts to collapse the neatly segregated spaces of the private and the public, of the purdah-nasheen (veiled) wife and the be-purdah (unveiled) tawaif.

Williams also writes about Khas Mahal, Wajid Ali Shah’s first wife (the first of his two nikahi, or high-status, wives). Describing her in an interview with me as a ‘tremendously creative, musical woman’, he says that she wrote more poetry and lyrics than her husband, who proudly collected them. She was also a participant in the elaborate theatrical productions that Shah organised. (‘She was in charge of costumes,’ says Williams.)

Williams has noticed a worrying tendency by art historians and collectors to uncritically label all visual art depictions of women singing and dancing as courtesans. ‘Some of them are just not courtesans. Many of them appear in zenanas, which courtesans quite often could not access.’

Instead, Williams offers three different categories of women music-makers and poets who are not courtesans—aristocratic women, women employed by noble women and women who performed in public for religious purposes.

Only a few years after the publication of Umrao Jaan Ada, a new kind of technology enters South Asian soil, and changes the performance, production and reception of music in profound ways.

Yet, established male ustads are suspicious of the gramophone, having guarded their musical knowledge in exclusive mehfils for elite patrons. Sometimes they are superstitious, believing in the claim that the new machine would steal their voices. Performing women stepped in where they would not, including the woman that Kidwai calls the first gramophone superstar, an Armenian woman by the name of Gauhar Jaan.

Gauhar adapted several styles of Hindustani music, including her repertoire of ghazal, thumri, khayal, and folk music to the tight time limit of a handful of minutes required by the machine. She was among the most famous to do so, but by no means the only one. Janki Bai of Allahabad, her junior, was just one more example of a woman who achieved incredible fame and success through the sale of their records. Both Gauhar Jaan and Janki Bai were invited to sing at King George V’s coronation in India.16

In order for people to distinguish between their records, these women singers shouted their names at the end of each recording: ‘My name is Gauhar Jaan!’

At the same time, even a successful artist like Gauhar, whose image was printed on matchboxes in faraway Austria, and who rode her tanga in defiance of the British through the streets of Calcutta, hankered for acceptance from two very different establishments. On the one hand, her records were inscribed with the word ‘amateur’ (as opposed, of course, to ‘professional’) lest she become the target of the reform campaigns that tawaifs were already facing. On the other hand, Dewan has written about how, as an Armenian, she paid Nanhua and Bachua Jaan, two famous tawaif sisters from Lucknow, considerable gifts in cash and kind in order to be formally adopted into their tawaif family.17

Yet, no matter how successful they were, many tawaif performers ended up in penury as a result of patronage running out, and entanglement in ruinous court cases filed by malicious people.

Amlan Das Gupta has written about how many even renowned tawaifs like Badi Moti Bai were found by Bengali singer and writer Reba Muhuri to be struggling financially towards the end of their lives.18

In Amritlal Nagar’s Yeh Kothewaliyan (These Women of the Kotha), we find that renowned singer Vidhyadhari Bai also lived in extremely modest circumstances despite the fame and respect she commanded as a younger woman.19

This particular aspect of many famous courtesans’ life stories finds a mirror in Umrao Jaan’s own financial decline after the Rebellion. Gauhar Mirza, a man in her household, robs her of some of her wealth, while the rest goes into fighting a court case against a patron who claims she is his wife.

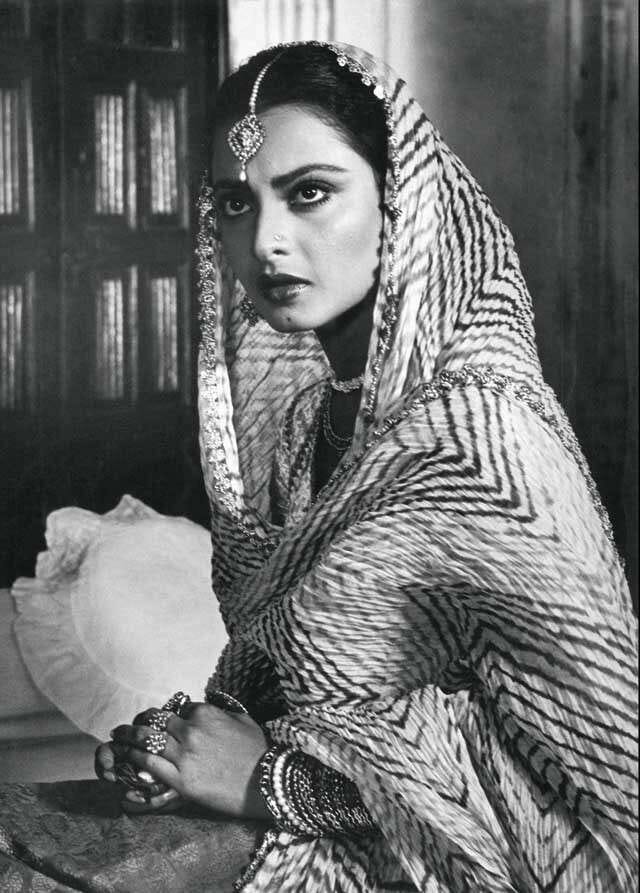

Umrao Jaan, the film, made in 1981, is its own text. Its feminist sensibility is overt, Saba Dewan tells me, which in Ruswa’s text is to be found by reading between the lines.

As a ‘Lucknow’ film, it is important because, unlike other films supposedly set there but filmed on sets in Bombay, it actually uses recognisable real-life Lucknow locations, says Kidwai, who is from the city.

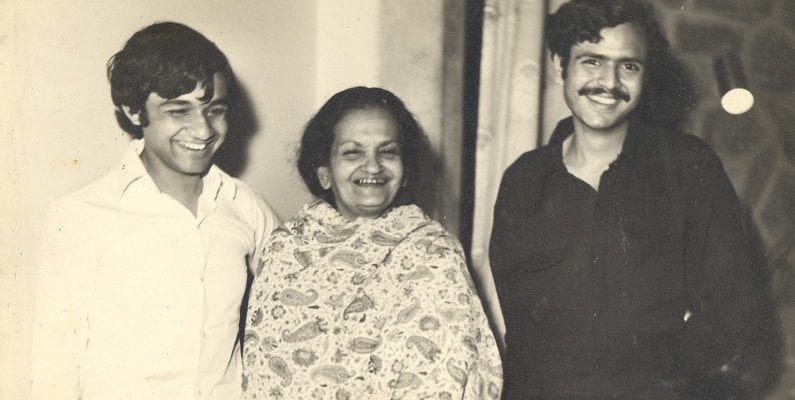

I went to one such real-life setting during a visit in 2019, when I first met Kidwai and interviewed him about two great tawaif singers, contemporaries based in India and Pakistan respectively—Begum Akhtar from Bhadarsa in Faizabad and Malka Pukhraj from Hamirpur Sidhar in Jammu, both of whom he knew in their lifetimes.

I also went to what remained of an erstwhile royal palace, where part of the shooting for Muzaffar Ali’s film had taken place. It was also a place where Begum Akhtar had come to perform for the royal household, and the prince, now a much older man, had accompanied her on the tabla. In one of the corridors of this palace is an incredible photograph, of a family wedding celebration, to which every well-known tawaif of the time had come to perform.

Over the years, the film has been cited by many writers as one of the major examples of the Islamicate courtesan film. Another famous example of this is, of course, the Madhubala-starrer Mughal-e-Azam, about the ill-fated Anarkali, who transgresses the norms of social segregation by falling in love with Prince Salim. There is also Pakeezah, released by Kamal Amrohi ten years before Muzaffar Ali made Umrao Jaan.

‘It’s much more allegorical,’ Morcom tells me of Pakeezah, starring Meena Kumari as the courtesan Sahib Jaan. ‘It’s about the dying of the courtesan tradition with the coming of modernity, symbolised by the train. There’s also Sahib Jaan’s love interest who is a forestry officer—employed by the government—so even though he’s from a zamindar family, he’s also representing modernity.’ It is in Pakeezah that we find the redemptive arc that has come to animate popular cultural imagination around the highly stylised courtesan heroine: marriage.

Through a series of fortunate accidents, Sahib Jaan escapes the loss of virginity that would have signalled her formal induction into the tawaif business, and eventually, with the permission of her love interest’s aristocratic family (of which she turns out to be a rejected daughter), marries him. Her name is changed to Pakeezah, or the Pure One. Before she marries, however, she dances on broken glass, so as to ensure that she does not dance again. Her feet have been the subject of particular fascination for her lover, who first glimpses them as she is asleep during a train journey. She awakes to find a note from him tucked between her toes.20

Kidwai credits Pakeezah with the creation of a new cinematic trope even within courtesan films—the ‘virgin tawaif’. ‘Since it took forever to make, the script must have been known to other scriptwriters, so this trope became classic even before the release of Pakeezah,’ he says. Even as the train does represent modernity, he thinks it harks back to the mobility of tawaifs. ‘After all, it is in a train that the hero first sees the heroine.’

In calling Umrao Jaan Ada a quintessential Lucknow story, though, what Lucknow are we referring to?

Himanshu Bajpai says that now Lucknowi culture of a certain kind—evoking a feudal past and starring elite Lucknowis—has become a ‘brand’. ‘Every story revolves around Nawabi culture—that is what is encouraged, and that is what becomes popular. Only the elite and “refined” get entry into this idea of Lucknow.’ He tells me the story of the tawaif Jali Khurshid, who was an expert in patangbazi, the art of flying kites. ‘She defeated many men in kite-flying. There’s a famous story about her, in which she was challenged by a nawab and in response she cut down seven kites, all the while sitting in her armchair.’

In focusing squarely on elite tawaifs who are fetishised for the value they provided to elite men—sitting with them, entertaining them using conversation and manners typical of high society—Bajpai says we lose the stories of rebellious and unusual women like Jali Khurshid. ‘And we also lose the stories of other women who practiced the same arts, but who lived more mundane lives, or were not as well known.’

Bajpai also finds the oft-repeated claim that young men from the nobility went to tawaifs to learn ‘tehzeeb’, or refined manners, suspect. ‘I’ve read a lot and looked for many references to this and I think it was another way for the elite to justify visiting tawaifs, and also to hide the ways in which tawaifs could be exploited. There are many stories of tawaifs who were mistreated by these elite patrons.’ He challenges the claim that there was once a time that they were uncritically accepted into mainstream society. ‘They never got mainstream recognition. If they had, wouldn’t they have lived in homes all over Lucknow? Why was there a special courtesans’ quarter in Chowk then?’

He feels that in focusing on this ‘limited, exclusive Lucknow where only upper-class and caste-privileged people are featured’, we lose the flavour and complexity of an endlessly fascinating city. ‘I also feel that this kind of lens has done a lot of damage to tawaif culture as well. It prevents us from seeing them as people. We only talk about the tawaifs who neatly fit into this idea of a courtly Lucknow.’ All the courtesan stories that do not fit so neatly into this mould are lost to the ether.

There is also the fact that Ruswa’s Lucknow in Umrao Jaan Ada is a kind of historical novel too, given that its author was born in 1858. The character of Umrao is older and is looking back at a period of time that Ruswa did not directly experience.

‘There is a larger trend of nostalgia that we have to keep in mind. People so often forgot that Wajid Ali Shah went to Kolkata; both he and Nawabi culture became the stuff of legend. It did not matter that he actually spent thirty years in a different city,’ Williams says. ‘There is the idea of 1857 being the end.’

Williams refers to a late-nineteenth-century Bengali travelogue he is currently reading, which talks about a visit to Lucknow and refers to Wajid Ali Shah, although he isn’t there anymore.

‘At the same time as Ruswa, you have Abdul Halim Sharar writing, and his work is just dripping with nostalgia for Shah’s Lucknow. Even though he himself grew up in Matiaburj, as far as he is concerned, it is like a ghost town of the real Lucknow. He is not alone in this.’

It is against this larger picture of nostalgia, not only in ours but in Ruswa’s own context, that we can fully read Umrao Jaan Ada. ‘The ghost of Lucknow is a heavy presence … The irony is that it was only a few decades later, and much of the culture they were being nostalgic about was not actually lost. Tawaifs were definitely still performing, although they were being attacked,’ Williams says.

Ruth Vanita, who in her study of Urdu Rekhti poetry from 1780 to 1870, found that courtesans were ‘female public intellectuals in urban India’,21 says that this idea of the courtesan film as ‘Islamicate’ is based on an overemphasis on the three films I have mentioned above. In a full-length study of 235 films that portray courtesan or courtesan-adjacent characters, Vanita has shown the syncretic and cross-community nature of tawaifs depicted on film:

‘The assumption that the cinematic courtesan is synonymous with Muslims involves downplaying numerous important courtesan films in which all the characters are Hindu and where Hindu practices and symbols are thematically and structurally central to the film.’22

The other problem with not seeing courtesan depictions from a wider lens is that we stay stuck in the idea that these are all tragedies. ‘There’s no sense of mundane normality. There’s no evidence I’ve seen that courtesans or sex workers just utterly and completely loathe themselves and feel engulfed in this terrible, terrible victimhood. This isn’t coming from them,’ says Morcom.

Vanita’s study is important for the way it moves us far beyond this stereotype of the beautiful but damned cinematic tawaif.

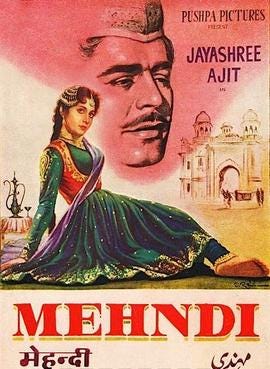

Umrao Jaan Ada has been adapted into film several other times, including some adaptations that are more faithful to the novel, such as Mehndi (1958). The Muzaffar Ali version, however, has endured in popular culture because of its aesthetic quality, particularly its Lucknow setting, art direction, cinematography, music, lyrics and costumes. It is widely remembered as a career-defining role for its star, Rekha, alongside whom many widely admired actors have been cast, including Farooq Sheikh, Raj Babbar, Naseeruddin Shah, Dina Pathak, and Shaukat Kaifi.

The film makes some major departures from Ruswa’s original text. Ruswa himself, as the person to whom Umrao is telling her story, disappears entirely. So does, therefore, the exchange of Urdu rekhta poetry between them that is so central to the way the novel is structured. Taking the place of this poetry, although not in such a neat way, is of course the exquisite soundtrack, with lyrics by Shahryar and music by Khayyam.

Dewan points out the central departure that the text of the film subtly makes—for the film, Umrao’s romantic relationships take centre-stage, especially the one with Nawab Sultan, played by Farooq Sheikh. Still, shades of the novel's many layers filter through.

For me as a viewer, three scenes stand out in the way that they frame Umrao’s story, and the points the film is trying to emphasise.

The film’s very first scene, containing its credits, is a song sequence with the only song that has lyrics scripted by someone other than Shahryar.

Ameeran, not yet Umrao, is being prepared for her engagement by the women in her family, who sing the popular Braj wedding song by Amir Khusro. The song is a considered choice, as a closer study of its lyrics (not all of them included in the scene) show. Kahe ko byahi bides? (Why did you marry me off so far away?) is a daughter’s complaint against her well-off father.

The daughter in Khusro’s song compares herself, in several devastating verses, to objects or creatures in her father’s home, her destiny yoked to his slightest whim. One verse directly speaks to the fact that the bride’s brother inherits the family home whereas she is simply sent away.

Ali and the script writers don’t need to rub the point in our faces—the harshness of her reality still endures. Ameeran is a child in a land where child brides are all too common, and a well-known wedding song communicates a daughter’s grief at being treated thus. Of course, it is also an augury—Ameeran will never be married, and will soon be wrenched away from her home into a completely different world that she cannot yet even imagine.

Our second pivotal scene comes in the middle of Umrao’s story. Nawab Sultan, Umrao’s beloved, has shot at a man who insulted Umrao in her kotha. He has stopped going to her salon, but they are able to meet at his friend’s home. However, she is insulted by the women at this home, and as she is leaving, she meets Sultan at the threshold of the house. She tells him to come to her salon if he wants to see her. He insists that he cannot go there, and she responds, ‘And I cannot come here.’

But it is the film’s final scene that arguably elevates the entire text. Umrao has witnessed the fall of Lucknow—and of Khanam Jaan’s establishment—as a result of the Rebellion. She has gained and lost two independent establishments of her own, in Kanpur and Faizabad. Umrao has now returned to Lucknow, in a city that will not, as the novel shows us, give her the same opportunity for social mobility and wealth as Khanam had enjoyed. She returns to the kotha and wipes the mirror, laden with dust, coming face to face with her own self. ‘She’s owning herself, and the events of her life,’ as Dewan says.

Yet it is Dewan’s own work that has moved things forward substantially as far as understanding real-life tawaifs goes, argues Morcom: ‘[Tawaifnama] is a social history of the north Indian performing arts. She’s also brought a sense of their mundane lives into the discourse. These courtesans weren’t all these tortured, beautiful, mysterious women. In portraying them as beautiful and sensual, these films glorify them and show them as wronged. They were wronged, but not in the way that’s been portrayed.’

In the course of researching this essay I couldn’t help but return to the question of what real-life courtesan performers working in films felt about these various representations. Once you start looking into it, dozens of names pour out, but for the purposes of this essay, I will speak about one—Jaddan Bai, recently depicted (albeit briefly) in Nandita Das’ Manto.

‘By the time Jaddan Bai died, in 1949, she had become a veritable institution of the Bombay film industry. (...) Legendary was her imperious manner, her ability to settle complex personal and professional industry disputes, her generous open kitchen, her penchant for colourful language, and the high premium placed on her advice and introductions,’ writes Debashree Mukherjee. 23

Her mother was Daleepabai, a tawaif from Allahabad, and Jaddan Bai was, Kidwai writes, ‘an extremely popular gaanewali’ who understood the possibilities that the world of cinema offered and embraced them. Mukherjee has analysed her multi-layered career as a ‘singer, actress, producer, director, screenwriter, composer’.

She founded her own production house, Sangeet Movietone, in 1936, becoming one of the first women to do so. (In fact, the first woman producer in the Bombay film industry was Fatma Begum, another tawaif performer.) Mukherjee writes about the difficult circumstances within which Jaddan Bai and her many colleagues were working:

‘The link between female performers and cinema was also entrenched in a deeply moralistic discourse. It is common knowledge that the earliest actresses on the South Asian film screen belonged to professional performative traditions like theatre, dance, and music. Such public women were greatly stigmatized and their liminal social status was the condition for their entry into the dubious new realm of cinema. At the same time, their presence exacerbated anxieties about the negative implications of this new medium. By the time talkie technology appeared on the scene, the industry needed these talented women more than ever but the dominant nationalist rhetoric of “respectability” and “self-improvement” pulled in the opposite direction. And, predictably, it was women and their sexualities that became the locus of nationalist concern.’

Jaddan Bai was already highly reputed before she entered the film industry, and as Mukherjee has said, closed out her career in similar circumstances of ‘fame and solid repute’. But it is ‘this middle period when she first entered the film industry’ in which Mukherjee argues ‘she must have struggled hard to rid herself of the tawaif tag’. She shares an anecdote in which a woman in Manto’s family railed against ‘the entire courtesan class’ directly to Jaddan Bai, who calmly told her at the end of this tirade of her own identity.

The first film released under the Sangeet Movietone banner is Talash-e-Haq (Search for Truth, 1935). The protagonist of this film is Feroza, an actress who leads young men astray and is generally shown to lead a ‘life of vice’. Mukherjee argues that, although in this and other films Jaddan Bai is ostensibly engaging in a ‘morality play’ narrative, this must be read against her own life and context. She emphasises that at this time, ‘...the women’s melodrama mode was internationally popular. This cinematic mode often featured ‘fallen women’ who were pitted against society due to their transgressive choices and behaviour. Late 1920s and early 1930s Hollywood saw the dominance of the fallen woman protagonist, who was either cheated or compelled into sexual compromise or was a debauched child of hedonism who could not help herself. In either case, the plot demanded that these heroines pay up their ‘wages of sin’ and end up single, broke, or dead.’

Mukherjee argues that far from being a straightforward story invoking nationalistic discourse, this film ‘can be read as a part of the transnational appropriations of the fallen woman melodrama’. She analyses another film, Madam Fashion (1936), in which the protagonist is so involved in a life of luxury and consumerism that she loses her family. Here, too, Mukherjee argues against a reading taken at face value, saying that the film gives space to explore the protagonist Sheila’s interiority instead of simply condemning her.

If, as Mukherjee argues, Jaddan Bai carefully built up ‘an elaborate star image of herself’, she built an even more enduring career for her daughter Fatima Rashid, popularly known by her screen name, Nargis. Kidwai argues that it was prejudice against tawaif performers that led to Nargis never receiving musical training. ‘With the success of Nargis, both as a star and a public figure, the cover up of the origins of these artistes was complete. The gana had been successfully withdrawn from the treasures bequeathed to a ganewali’s daughter,’ writes Kidwai. But Jaddan Bai succeeded, spectacularly so, and Nargis flourished. Her family continues to hold major sway in the industry to this day.

It can all be traced back to Jaddan Bai, who had the foresight to leave a flourishing career in Calcutta, and choose to start all over again in Bombay films. It is a remarkable story that needs further research, which is likely to throw up many more examples of the ways in which tawaif performers ingeniously navigated the circumstances they were thrown into.

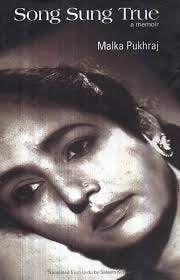

To return to the question we began with, authorial authenticity, if that is really what we are after, then why isn’t the only known memoir by a tawaif a bestseller?

Almost a century after the one that Umrao Jaan’s tale is set in, comes the story of Malka Pukhraj.

Born in the early 1930s in a village in Jammu, the daughter of a failed courtesan, Malka rose in eminence early. The rigorous training her mother ensured for her led to an official position—when she was all of nine—at the court of Hari Singh in Jammu and Kashmir.

Malka then moved to Pakistan and made a name for herself as a salon-based performer who was highly in demand, and worked in radio and films. She married a ‘respectable’ man who did not prevent her from singing. Malka continued to sing and be creative until the very end, and even though her family was against the publication of her memoir, found a way to ensure it was published in India.

Her collaborator and the person who actually sifted through her handwritten notebooks was none other than Saleem Kidwai. He reached out via a friend in Pakistan to ask if Malka would consent to an interview about her illustrious contemporary, Begum Akhtar. In return, he received copies of the notebooks in which she was painstakingly, and against all odds, writing a forthright and illuminating account of her life as one of the last famous tawaif performers.

Kidwai flew to Pakistan, and worked with an ailing Malka (with the support of her granddaughter, Farazeh Syed) to edit and accurately translate the memoir, which was published by Zubaan Books in India in 2003 as Song Sung True: A Memoir. At the time it came out, Kidwai wrote a detailed essay about the value of this book, which talked about Malka’s time as a child in Jammu and then in Hari Singh’s court, her relationship (it was paternal) with the king, the slanderous abuse she suffered as a Muslim performer in the court, her performances in various princely states, including a meeting with the abusive ruler at the Patiala court, her complex relationship with her mother, her long courtship and relationship with the man who became her husband, her family life and her life as a famous performer in Lahore.

Unlike Begum Akhtar, whom Kidwai has called ‘a biographer’s nightmare because of her need to live her life as a series of myths’, Malka has been exceptionally forthright. This is a literary account by a tawaif about her own life, not a literary representation by others—although even with this account, and all that it offers us, we have to bear in mind that Malka can only speak to her own unique life and experiences, and go against a cultural compulsion to conflate all tawaif histories. As Morcom argues, ‘Often people who write their own stories are larger than life people themselves, and even they don’t represent the whole community. Binodini Dasi (the Bengali theatre actress who wrote two autobiographies) is probably an example of this.’

In his essay at the time of its publishing, Kidwai correctly called the book ‘pathbreaking’, and professed the certainty that ‘whenever her original manuscript is published, it is sure to find a respectable place in Urdu literature’. The original, titled Bezubani Zubaan Na Ho Jaaye (Lest Silence Become Eloquent, as the newspaper Dawn sensitively translated the title), was finally published in the original Urdu in Pakistan only in 2021.

Kidwai’s English translation has, in India, gone out of print, making it near impossible to access a copy.

Ruswa’s Umrao is no straightforward text. It begins with that fixture of the Urdu literary scene—a mushaira—in which the author is himself a character. Several scholars, including Frances Pritchett, have emphasised the importance of separating the writer Muhammad Hadi Ruswa from the narrator-character Mirza Ruswa.

Ruswa and his friends, engaged in reciting verses in the course of this gathering, overhear a voice praising a couplet he has read out. It turns out to be the courtesan Umrao Jaan, whom Ruswa had once known and is now reunited with. Upon his urging, she joins the gathering, recites her verses and is pushed to share her own story.

This narration Ruswa creates into a manuscript without her knowledge or consent, and only shows it to her when he has finished it. The novel is interspersed with poetry; each chapter begins with a couplet that poetically mirrors it.24

One popular translation, by Singh and Hussaini25, entirely omits this crucial mushaira chapter, which is really Ruswa’s framing device for Umrao’s entire story. The last chapter features Umrao’s own anger at Ruswa’s trickery, followed by her admission that, although she intended to tear up the manuscript he had handed to her, she found instead that she could not stop reading it. This is followed by various meditations on the nature of love, of gender and gender norms, and exhortations to tawaifs regarding the faithlessness of men.

Some scholars claim that interviews and archival material show that Umrao was indeed a real person who told her own story to Ruswa, which he noted down. Some have even gone to the extent of saying that this or that grave in Lucknow or Banaras is hers.

This is the point at which things get thorny, because the problem with taking Umrao Jaan’s story literally is that we accept, wholesale, all of the elements that Ruswa has included for the sake of his plot. This is then taken as evidence of how the lives of tawaifs were lived in that time and place. ‘People write about courtesans using Umrao Jaan as a really pukka source,’ as Morcom puts it.

Pritchett has cited evidence to show that several historical claims made in the novel are simply inaccurate.26

Chief among these is the claim that Bahu Begum’s maqbara, the monument at which Ameeran’s father is said to be employed in the 1840s, was only completed and able to employ people in the 1850s.

Pritchett has also done a close analysis of all the coincidences and inconsistencies in the actual narrative—this includes some events closely mirroring each other, such as Umrao’s reunion with Khurshid Jaan, Ram Dei and Nawab Sultan in quick succession, or the circular arc which shows Dilawar Khan, the man who trafficked Ameeran, as being finally punished by the legal system towards the end of the novel. Any one of these events would have been extraordinary in a real, lived life, but are not surprising in a tragedy or a melodrama, both of which are modes Ruswa employs in the writing of Umrao Jaan Ada.

Scholars who argue that Umrao was a real person rely partly on the fact that Ruswa got a lot of tawaif context right (though in this they ignore the ways in which he overemphasised the melodramatic at the expense of the mundane). There is no doubt that he knew courtesans. It is totally possible, Kidwai says, that Umrao is loosely based on a real person, or several real people he knew. ‘But that isn’t the same as saying that there was a real Umrao that lived in X time at X place. If she’s such a famous courtesan and poet, where’s her diwan? Why don’t we hear of her independently of the space of the novel?’

That is also what Himanshu Bajpai means when he says both schools of thought are accurate, and both are inaccurate. The truth lies in the liminal.

What Bajpai finds valuable about the novel is that it treats Umrao like a person. ‘This lens is missing in so many stories that have been told about tawaifs since then. There has been a large gap in literature after Umrao Jaan Ada that looks at the emotional journey, including the pain, that a tawaif might have experienced in her time.’

He tells me about a filmmaker who had come to see him. ‘He wanted to make a film on Begum Akhtar. The first thing he asked me about her life was to tell him the story of how she was harassed by a raja. When he asked me that, I got up and left. I did not want to participate in yet another representation that sensationalises real women’s lives, and does not look at them as full human beings,’ he says.

Dewan also finds the exploration of feminine subjectivity in Umrao Jaan Ada exceptional, especially in the hands of a nineteenth-century writer who identified as a man. ‘What was really interesting to me about the novel itself was its refreshing candour,’ Dewan says. ‘There is some moralism, but it’s almost pat. Umrao is saying it because she’s expected to say it.’ She places Umrao’s story in the context of the popular trope of the nineteenth-century confessional tales by so-called ‘fallen women’, in which the act of speaking about their lives becomes redemptive. ‘There is a certain show of contrition, which may not ring very true—but the candour, humour and exultation with which she talks about her own life and desires stand at odds with the repetition that she is a sinful woman who needs to redeem herself.’

This duality Dewan speaks of comes through in the narrative often, especially in the bantering conversations between Ruswa and Umrao. Sharon Pillai, in an illuminating reading of the making of the novel, writes of it as ‘… a consciously contrived text straining after a novel poetics of expression, a poetics of indirection, which given the character and the times makes especial historical and situational sense. The novel also constitutes a significant bid at aesthetic experimentation in the face of prevailing indigenous and colonial modes of narrativity, something for which Rusva is not always given nearly enough credit.’27

At the same time, we cannot forget that this is a morality tale. As Sarah Waheed argues: ‘Umrā’o Jān is allowed entry to the respectable society inhabited by Ruswa only as a reformed, repentant woman.’

Pillai has criticised scholars’ ‘fixation on realism’, which has limited analyses to three positions—the text as a historically ‘real’ auto/biography, the text as an accomplished realist novel, or the text as a flawed and unrealistic novel. ‘But do these arguments exhaust the narrative possibilities of Umrao Jan Ada? Even if correct are they sufficient?’ asks Pillai.

In asking these questions she also re-emphasises the clever literary game that Ruswa is playing with his readers, deliberately muddying the waters to keep them wondering whether his claims that he is writing about a real person are true.

In this, Pillai agrees with other critics about his aim—greater financial security through the success of his work. This is especially in light of the fact that his peers Nazir Ahmad and Abdul Halim Sharar had ‘captured the market for a certain type of didactic literature, and popular fiction, respectively’.

Instead, Pillai offers a new way to look at the text, calling it ‘a performance of mushaira in novel form … an intricate tango of rekhti and rekhta.’ ‘Rekhti’ was Urdu poetry written mostly by men in the voices of women, usually courtesans, whereas ‘rekhta’ was the formal Urdu poetic register practised by most poets. In Pillai’s reading, it is Ruswa, by pushing for personal details and a more intimate account, who is engaging in literary rekhti, while Umrao—‘poetic, allusive’—is engaging in rekhta. Pillai concludes that if Umrao’s narration is rekhta, ‘… it is in effect a ghazal’.

Thus, because it is a novel masquerading as a memoir, as a tragedy, as a melodrama, as an offering by a writer of popular fiction and as a ‘mushaira in narrative form’, as Pillai suggests, there are many ways—not all of them complementary—in which Umrao Jaan Ada may be read.

Pillai resolves the knotty question of veracity and authorship by evoking exactly this scattering of possibilities. ‘It’s not supposed to be taken at face value, or only at face value. Instead, interpretation is required for better appreciation of its fragmental offerings’.

She also answers a question asked by Jain: ‘Do we treat her as a liberated woman or a victim of society?’

‘This would have been a valid enquiry had it not been for a serious oversight: Umrao Jan Ada is neither Umrao Jan nor Umrao,’ is Pillai’s response.

Instead of looking at Umrao Jaan as a ‘clear-cut realist novel as Ruswa claims’, Pillai instead characterises Umrao Jaan Ada as ‘a boldly experimental novel in form and telling’ and a ‘chiaroscuro narrative that tantalises with the promise of fact, but delivers alluring fiction’.

I think there is a case to be made for liberating Umrao Jaan Ada from the burden of history. By recognising a work of fiction for what it is, we allow ourselves to have a relationship with this particular character and her story on their own terms. We allow ourselves to find our own biases and fervours in the conceits of the storytelling, and in the reception to it.

We allow ourselves to discover the dozens of stories, so different from hers—both historical and fictive—that are just now being discussed openly, or waiting to be discussed. We allow ourselves also to place flowers on the ellipses of history, all of the places in which countless stories were deliberately erased, or innocently but irrevocably forgotten. We can acknowledge what we cannot recall.

Also, we can come away from Umrao’s tale marvelling at the mysteries of circumstance that allow any piece of literature to endure. We can watch Rekha on film knowing we are not watching a documentary. Having done that, we can seek after more stories that expand our worlds, and let all of these stories breathe—hers, and ours.

Na poochho nama-e-aamaal ki dilawezi

Tamaam umr ka qissa likha hua paya

(How to describe the beauty of this book of deeds?

In it, I found inscribed the chronicle of my life.)

– Mirza Muhammad Hadi Ruswa, Umrao Jaan Ada

Note from the author:

This essay was first published by Westland Publications in the form of an e-book in July 2021.

I would like to thank Saleem Kidwai, Saba Dewan, Himanshu Bajpai, Katherine Butler Schofield, Richard David Williams and Anna Morcom for granting me interviews towards its writing.

I would like to thank Ajitha GS for originally commissioning it.

Shreya Ila Anasuya is a writer and researcher from Calcutta, India. Her award-winning fiction appears in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and Strange Horizons, among others, and she is a widely published writer of non-fiction.

For more about Shreya’s work, or to get in touch, please visit www.shreyailaanasuya.com.

‘Ruswa’, literally ‘Disgraced’, was Mirza Muhammad Hadi’s ‘takhallus’, or pen-name.

M. Asaduddin, ‘First Urdu Novel: Contesting Claims and Disclaimers’, Annual of Urdu Studies, Vol. 16, 2001.

Muhammad Hadi Ruswa, Khushwant Singh (trans.) and M.A. Hussaini (trans.), Umrao Jaan Ada, Orient Longman, New Delhi, 1961.

Veena Talwar Oldenburg, ‘Lifestyle as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow, India’, Feminist Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1990, pp. 259–287.

Muhammad Hadi Ruswa, Krupa Shandilya (trans.), Taimoor Shahid (trans.), The Madness of Waiting / Junoon-e-Intezar, Zubaan, New Delhi, 2015.

Katherine Butler Schofield, ‘The Courtesan Tale: Female Musicians and Dancers in Mughal Historical Chronicles, c.1556–1748’, Gender & History, Vol. 24, No. 1, April 2012, pp. 150–171.

Amelia Maciszewski, ‘Tawa’if, Tourism, and Tales: The Problematics of Twenty-First Century Musical Patronage for North India’s Courtesans’ in Martha Feldman and Bonnie Gordon (eds), The Courtesan’s Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, OUP, USA, 2006, pp. 332–352.

Sarah Waheed, ‘Women of “Ill Repute”: Ethics and Urdu Literature in Colonial India’, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 48, No. 4, 2014, pp. 986–1023.

Saba Dewan, Tawaifnama, Context, Chennai, 2019.

Veena Talwar Oldenburg, ‘Lifestyle as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow, India’, Feminist Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1990, pp. 259–287.

Anna Morcom, ‘Courtesans, Bar Girls, Dancing Boys and Bollywood Dance’, https://www.india-seminar.com/2015/676/676_anna_morcom.htm.

Saba Dewan, Tawaifnama, Context, Chennai, 2019.

Regula Burckhardt Qureshi, ‘In Search of Begum Akhtar: Patriarchy, Poetry, and Twentieth-Century Indian Music, The World of Music, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2001, pp. 97–137. Also see: Shreya Ila Anasuya, ‘Memories of Akhtari’, Mint Lounge, 5 October 2019, https://www.livemint.com/mint-lounge/features/memories-of-akhtari-11570190924213.html.

Saleem Kidwai, ‘The Singing Ladies Find a Voice’, Seminar Magazine, https://www.india-seminar.com/2004/540/540 saleem kidwai.htm.

Richard David Williams, ‘Songs between cities: Listening to courtesans in colonial north India’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27(4), 2017, pp. 591–610.

Shreya Ila Anasuya, ‘Dastaan-e-Dilrubai: Janki Bai's is a name that rings in history, memorable as her bright voice’, Firstpost.com, 11 May 2020, https://www.firstpost.com/long-reads/dastaan-e-dilrubai-janki-bais-is-a-name-that-rings-in-history-mem orable-as-her-bright-voice-8344781.html.

Saba Dewan, Tawaifnama, Context, Chennai, 2019.

Amlan Das Gupta, ‘Women and Music: The Case of North India’, in Bharati Ray (ed.), Women of India: Colonial and Post-Colonial Periods, Centre for Studies in Civilization, New Delhi, 2005, pp. 454–84.

Amritlal Nagar, Yeh Kothewaliyan, Lokbharati Prakashan, Allahabad, 2008.

Anna Morcom, Courtesans, Bar Girls & Dancing Boys: The Illicit Worlds of Indian Dance, Hachette India, New Delhi, 2014.

Ruth Vanita, Gender, Sex, and the City: Urdu Rekhtī Poetry in India, 1780-1870, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2012.

Ruth Vanita, Dancing with the Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema, Bloomsbury Academic, New York, 2019.

Debashree Mukherjee, ‘Jaddan Bai and early Indian cinema’, in Jill Nelmes & Jule Selbo (eds), Women Screenwriters: An International Guide, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 70–81.

To see it slightly differently, Pillai (2014) writes 'Every chapter of the novel begins with a couplet that it loosely vivifies in prose.'

Muhammad Hadi Ruswa, Khushwant Singh (trans.) and M.A. Hussaini (trans.), Umrao Jaan Ada, Orient Longman, New Delhi, 1961.

Compiled by F.W. Pritchett, ‘Some of the many signs that we are reading a NOVEL, not an autobiography’, Fall 2008, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/umraojan/00inconsistencies_fwp.html.

Sharon Pillai, “Tell…the truth, but tell it slant”: Form and fiction in Rusva’s Umrao Jan Ada. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. 2016;51(1):110-126. doi:10.1177/0021989414553241